-

Fri, 05 Dec 2025

Best Delegates Award for St Swithun’s at Oxford Global MUN

-

Wed, 26 Nov 2025

U4 Take on Paris: Crêpes, Culture and Countless Steps

-

Wed, 26 Nov 2025

St Swithun’s Chef Awarded Junior Chef of the Year

-

Thu, 20 Nov 2025

Building STEM ambassadors of the future at St Swithun’s Prep School

-

Thu, 18 Sep 2025

St Swithun’s celebrates 25 years of Greenpower

-

Mon, 01 Sep 2025

Starting boarding? Top tips from current boarders

-

Tue, 26 Aug 2025

Triple Triumph for St Swithun’s Linguists in National Competitions

-

Thu, 21 Aug 2025

St Swithun’s celebrates the school’s highest ever top GCSE grades

-

Wed, 20 Aug 2025

Our Prep Outdoor Explorers is Award-Winning – So Why Learn Outside?

-

Thu, 14 Aug 2025

St Swithun’s A-level students celebrate a record-breaking year

-

Tue, 24 Jun 2025

Author Thomas Harding visits St Swithun’s School for academic lunch

-

Tue, 27 May 2025

St Swithun’s student founds Jane Austen book club at school

-

Wed, 09 Apr 2025

St Swithun’s students join the fight against period poverty

-

Mon, 31 Mar 2025

Headmistress Jane Gandee stands up for single-sex education

-

Thu, 20 Mar 2025

Sixth form student is a finalist at national maths competition

-

Wed, 12 Mar 2025

St Swithun’s prep win regional netball title and silver at nationals

-

Wed, 05 Mar 2025

Do girls perform better in an all-girls school?

-

Sun, 02 Feb 2025

St Swithun’s sixth-form students celebrate Oxbridge offers

-

Wed, 09 Oct 2024

Sporting Super Saturday for St Swithun’s

-

Thu, 22 Aug 2024

St Swithun's School Celebrates Impressive 2024 GCSE Results

-

Thu, 15 Aug 2024

St Swithun’s students celebrate excellent A Level results

-

Mon, 15 Jul 2024

St Swithun’s Challenge: A Community Triumph

-

Mon, 01 Jul 2024

Former Head Girl Jamie See on her time at St Swithun's

-

Fri, 21 Jun 2024

Equipping St Swithun’s girls for a secure future

-

Tue, 04 Jun 2024

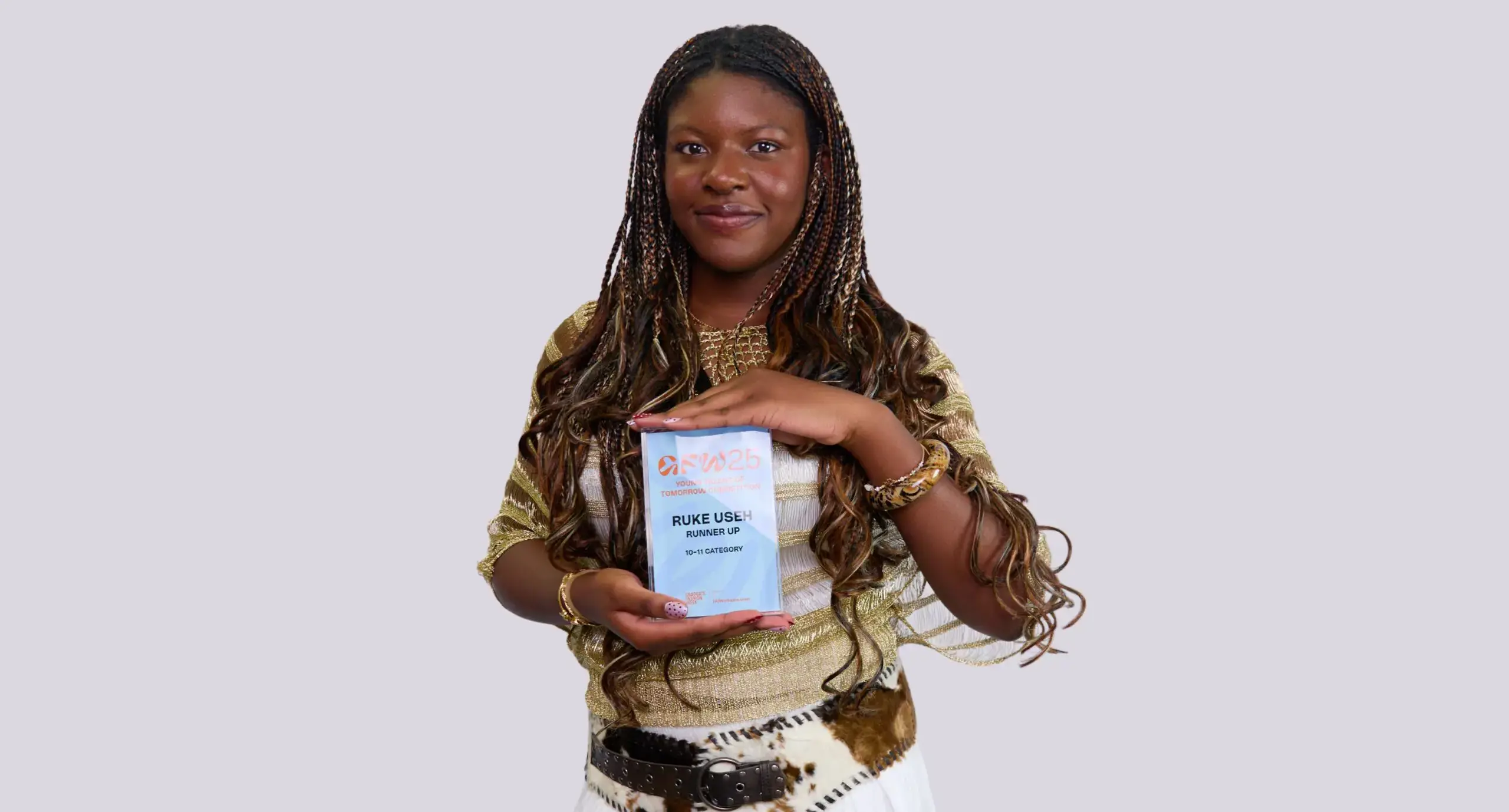

St Swithun’s Write Well Competition Crowns Winners

-

Sun, 05 May 2024

St Swithun’s School celebrates its 140th birthday in style